Note— I wrote this article on October 24th for an international news media brand after an editor reached out asking for me to write a call to queer people to be in solidarity with Palestine. After receiving backlash for publishing their Pro-Palestinian pieces, the magazine decided that they weren’t going to publish the piece. After publishing their pro-Palestinian stance the magazine lost over seven figures of funding and had to hire a Crisis PR Media team due to threats that they were facing for their stance.

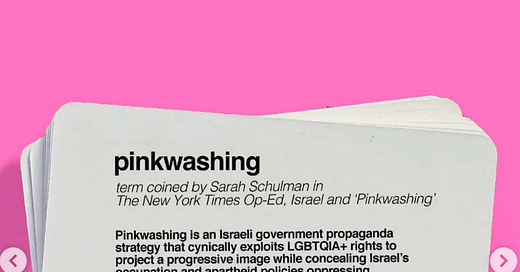

I’m going to publish the piece here, after the ordeal. I’ve been extremely disappointed with the way major Queer and Gay newspapers haven’t been covering what is happening in Palestine, due to pink-washing campaigns.

In reading this, please take into context that this was originally written on October 24th.

I love being queer. Fifteen years ago I don’t know if I even thought that it would be possible for me to write that sentence and claim it. But here I am, knowing with every fiber in my being that my queerness has allowed me such depth, the possibility to see beyond the structures society told me was acceptable love, to move beyond, into a possibility of care that’s not defined by the state or any of its apparatuses. Being queer has led me closer to freedom than I thought possible, closer to defining my own life on my own terms.

“Queer' not as being about who you're having sex with. That can be a dimension of it,” bell hooks says. “But 'queer' as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and that has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.”

There are so many layers as to what “queer” means. Ultimately, it’s an umbrella term that’s used to hold so many differing identities. There are an infinite number of ways to be queer, and I often see uniting under a queer umbrella as a label that helps assert myself as a person who loves and has intimate relationships that are not in alignment with heterosexuality, and as a political framework that has been created and defined by activists and abolitionists like hooks to assert a responsibility in refusing oppressive forces in order to shape a new world and future of freedom and collective liberation.

I was in middle school on the east coast when September 11th happened. I remember how it felt to go from being seen as a baffling other to being seen as a terrorist. Grown adults looked down on me with vitriol when I was twelve. Boys at soccer practice threw glass bottles at me just for looking like a Muslim. My life has been marked by the dehumanization of Western media, by how I’ve had to prove that I am a human.

This is what we see happening now.

In the efforts of its own imperialist project, the US is funding this violent mobilization against Palestinian people and their neighboring regions. Western media continues to talk about what’s happening in Palestine and Israel as a matter of “both sides.” It’s not. What we are witnessing now is the beginning of a genocide. As queer people, we should be among the first to stand up against this.

In 2010 I studied abroad in Jordan and traveled into Palestine a few times. I was ruthlessly questioned and disenfranchised by the IDF at various checkpoints. I also lost access to my bank account/ atm and cell service while traveling. In my moment of desperation, Palestinians took care of me and my friend, gave us food and a roof. They demonstrated generosity, humanity and what it means to act as a collective and create beyond the walls we'd been given.

I have so many beautiful memories from Palestine and so many tough ones too. I’ve seen firsthand the ways Palestinians have been denied access to water, use of the roads, and live in food deserts while the occupiers of their land had access to abundance. This apartheid regime the Palestinian people are under has existed since 1948 after the Nakba, the ”catastrophe.” 15,000 Palestinians were murdered by Zionist militia, 700,000 Palestinians were forced to flee their home, and 400-600 Palestinian villages were destroyed. While indigenous Palestinians were forcibly expunged from their homeland, Israel settled a colonial state.

Over this now 75-year history, the Israeli state has systematically violated the basic human rights of the Palestinians beholden to its militia, restricting freedoms as simple as voting, travel, and access to water. Palestinian people are criminalized for throwing stones, while the Israeli Defense Forces routinely bombs Gaza. In 1967 the Israeli Military consolidated power over all Palestinian water resources and issued laws that made it impossible for Palestenian’s to access more water without obtaining Israeli permits. If this was an equal conflict, Israel wouldn’t have been able to do this. However, the Israeli government’s actions have, for decades, been built around the suppression of Palestinian people. When we consider the power dynamics in the situation, who has it?

Audre Lorde writes, the United States “are citizens of the most powerful country in the world, a country which stands upon the wrong side of every liberation struggle on earth.” This includes our own liberation struggle as queer and trans people.

The call has been issued to stand in solidarity with the liberation struggle of Palestine. It is our duty as queer people to show up, and to show what being queer really means.

As we know, governments are not their people. The Israeli government is not indicative of Jewish people or Israeli people at large. Palestinians cannot all be conflated with Hamas nor should they be killed for Hamas’ crimes.. Both the people of Palestine and the people of Israel deserve to have the freedom to thrive, to love, to be alive. A truly queer vision for justice doesn’t include the harming of any of these civilians. Many Western media narratives have weaponized grief for military state propaganda, despite the thousands of Israeli and Jewish demonstrators who have been standing with Palestine, demanding a ceasefire, and who understand the nuance and truth of this crisis.

What we see happening right now is not a conflict between two state actors. This is a genocide. This is a genocide ongoing for decades, where an entire population is being starved out and murdered with unrelenting vigor.

Those who like to toss around the word “decolonization” need to stand up. To me, decolonization is not an intellectual enterprise but a spiritual one. Much like queerness, it challenges us to detangle our programming, to learn from our ancestors and the things they have shame around, transmuting pain into fuel for new worlds. An embodied relationship with decolonization allows us to actually move things out, through our body, through our history, ancestry and family line. It means working with somatic practices so our bodies show up differently in the world.

A former professor of mine, Corey Walker, taught me about decolonizing philosophy, and the world views and biases inherent in philosophical thinking. One of the premiere ideas in Western philosophy is Descartes idea of ‘I think, therefore I am.’ That privileges the mind and the conceit of analytics as the basis of humanity. And how, so much of western cultures are oriented around this, to the point where the idea of who can think is policed, limited, and debated in order to control the status quo of who can be a human. Because dominant society can limit who has the right to think, they can also limit who has the right to be seen as human.

An alternative in decolonization theory is Frantz Fanon’s idea: “Oh my body, make of me always a man who questions!” And this idea that from the body, from the spiritual and energetic knowledge of the body, comes the hope and longing of the practice of thought, and specifically, the practice of questioning. That to question is central to our evolution and growth, as is the deep prayer to always value and put into practice that questioning, and that is only possible with a body. So with a body, and with centering our bodies, we actualize our humanness, our spiritual evolution, our ability to change, our ability to grow.

By centering the body, we also see whose bodies ‘count’ in terms of seeing a death toll and whose doesn’t. When white phosphorous bombs are being dropped on Gaza, which is a war crime as defined by the United Nations, and the US still supports Israel, we see whose bodies matter.

When I tap into the archetype of loving courage, of loving power, I feel the sun. I feel how much it loves, how it spreads its light all around with warmth. How big the sun’s dreams are, touching all of us, uniting and bridging us. When it rests, it shines in other places, so bright it insists on reaching everyone. This is a reminder of what we can all be, what we can embody.

In my own queer decolonization work, I’ve stopped believing in state structures to save me or shape my identity. Statehood claims it protects the people who live within and beyond its bounds, but this is rarely true. For queer people to align their beliefs or personhood with the state would be hypocrisy. We have always sought ways to circumvent the state if we’re not already in direct opposition to it. The US showcases this intense hypocrisy, and much like the Israeli state, is often more interested in furthering its state power than the lived reality of its people. But that’s what happens when you have a nation that is built on genocide and slavery and still refuses accountability to its past atrocities.

This is not a cycle my queer body consents to, it’s not one that we as queer people should wish to continue. In a world where it is clear that the nation state is an outdated model that cannot hold us down, that cannot protect us, I ask: what do we owe each other? What do we owe the land? How do we protect each other, and the land, in this increasingly turbulent time?

Whose bodies matter matter? Whose love matters? Whose queerness matters? Isn’t it our job to fight for the safety of queer people everywhere, their right to live and love?

From an instagram account called Queering The Map, which is full of anonymous accounts of queer stories on a map, one user wrote from Gaza, “Idk how long I will live so I want this to be my memory here before I die. I am not going to leave my home, come what may. My biggest regret is not kissing this one guy. He died two days back. We had told how much we like each other and I was too shy to kiss last time. He died in the bombing. I think a big part of me died too. And soon I will be dead. To younus, I will kiss you in heaven.”

Another thing the sun teaches us: how to dream big. In that dreaming, I see a beautiful home for Palestinians, where they don’t have to worry about bombings, access to roads, water, and food. To churches and mosques and hospitals. To be able to travel and see their families and friends abroad and know they can always return. Where families and people live. Where the most pressing thing on people’s hearts is the fact that some random person ghosted them. Where the Jewish people are also safe, loved, and have access to abundant community.

Where others resort to state-sponsored narratives, queer people can see beyond. If we can step into courage. The immediate calls to action from Palestinian people is to call your reps to demand a ceasefire, an end to Israeli occupation of Palestine, and for humanitarian aid. Demand your reps put pressure on Israel to restore internet back to Gaza. And be loud: talk about it with everyone, educate yourself, show up to protests and show that the world stands with Palestine.

An Egyptian podcaster Rahma Zein confronting CNN on their unethical reporting. Courage. Thousands of Jewish people occupying Congress and demanding a ceasefire now. Courage. Egyptian truck drivers waiting days at the border to deliver aid in the face of air strikes. Courage. Former IDF soldiers who are speaking out about the state’s atrocities. Courage. Jewish people at protests holding signs that say ”Not In Our Name.” Courage. Gabor Mate, a Holocaust survivor, speaking up against Zionism. Courage. The people of Gaza, reporting live from their phones so the world can see what is really happening. Courage. People storming the Egypt-Gaza border crossing, trying to open it by sheer force. Courage. The doctors in Gaza operating, still, with such little fuel and by flashlight. Courage.

Radical queerness rests on a foundation of valuing human life, of each other’s contributions, where we can honor that, where we can nourish, where that can grow. All systems of oppression are linked together, and so are the liberation movements that dream against them. Believing in a shared future that some call ‘naive’ is queer, in and of itself. So many others share this dream with us collectively. We dream it with strength, with courage, with the conviction of the sun.